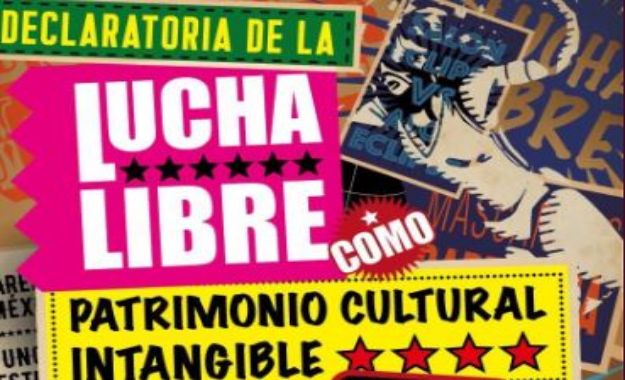

One year ago today, lucha libre was declared “Intangible Cultural Heritage oof Mexico City” based on the criteria put forth by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Now, one year later, we wanted to take a moment to answer a question we often receive by more casual fans of the sport: What makes lucha libre so important to Mexican culture?

It is not always so easy to understand, especially with how the version of professional wrestling in the United States is looked at as quite lowbrow and un-cultured by much of the population.

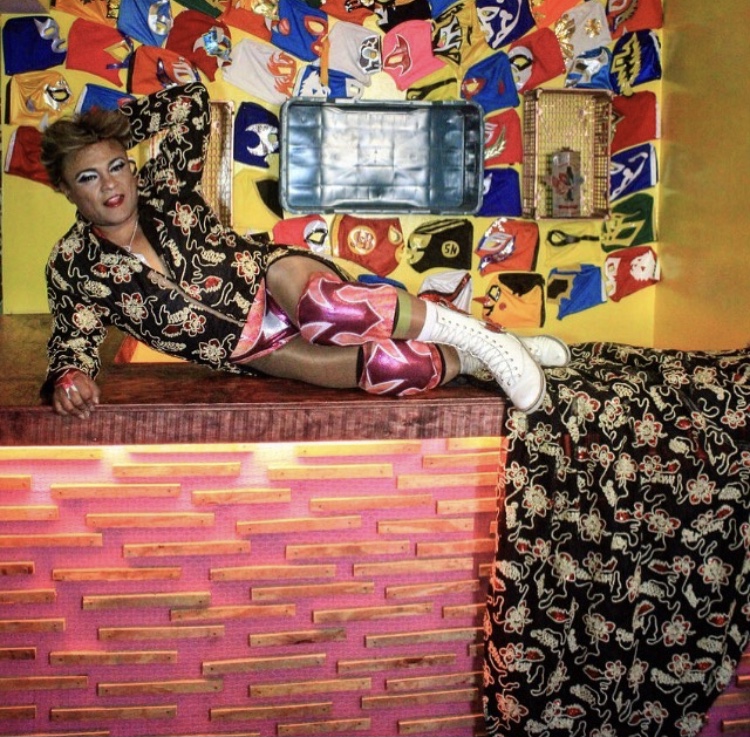

PHOTO: Daniela Herrerias

It was in 1994 when I was first introduced to professional wrestling–the first time I was exposed to the likes of Hulk Hogan, Macho Man, and Lex Luger. These men were typical of what being a wrestler meant at the time, and, to American audiences, largely still does: huge men with huge muscles, lumbering around the ring and slamming each other.

But four years after that first taste of professional wrestling, I saw another side of wrestling–something utterly alien to the type of giant muscle-men I was used to seeing. Watching a taped copy of WCW’s Road Wild, I saw performers such as Rey Mysterio Jr., Psicosis, and Juventud Guerrera, all of them noticeably smaller, faster, and far more agile than your typical American wrestler. I had been exposed to lucha libre for the first time, and that experience–the memory of how different it was compared to what I was used to, stuck with me for the rest of my life.

Professional wrestling may have its roots in the United States, but it’s grown well beyond these shores since then. And in every country it’s touched, it has changed into something unique to that culture–from the slower-paced, more cerebral catch-as-catch-can grappling of British wrestling, to the hard-hitting MMA fusion of Japanese puroresu, wrestling is always evolving. And perhaps nowhere is that idea more prominent than when it comes to Mexican lucha libre.

Combining the rhythm and grace of a dancer, the death-defying acrobatics of a Cirque du Soliel gymnast, and the hard-nosed toughness of a more traditional martial artist, lucha libre when performed well resembles nothing so much as an elaborate, well-choreographed dance routine, or an on-wires fight scene in a kung-fu action movie. Indeed, while American audiences seek to lose themselves in the spectacle of the action, and Japanese fans treat their matches more like legitimate martial arts contests, Mexican audiences know luchadores’ acrobatics aren’t realistic fighting moves. Lucha libre audiences suspend their disbelief for the duration of the show, and as such, they allow themselves to believe that performers can almost fly.

PHOTO: Daniela Herrerias

Accordingly, the training regimen for a prospective luchador is grueling in the extreme, with some performers beginning their training as young as childhood. In fact, unlike in other countries’ variations of professional wrestling, luchadores are required to pass tests given by their local governments, to verify their training and to make sure they can perform the art authentically and safely.

Physically, the main differences are obvious–performers tend to be smaller, lighter, and more athletic than in other countries. But even beyond that, the training that luchadores receive is unique to lucha libre, with many moves simply not seen outside the style–at least not until it began to proliferate onto American television. There are countless examples of the physical differences between lucha and other styles, but three in particular stand out.

Firstly, lucha libre is known for “working left”. What this means in practical terms is, rather than leading with the left foot and left hand, in typical fighting stance for a right-handed competitor, luchadores lead with the right foot and the right hand. Miscommunication on that simple fact is widespread, and can ruin chemistry between two otherwise quite compatible wrestlers faster than almost anything else (imagine trying to drive a car with not only the steering wheel on the wrong side, but the brake and gas switched, and the turning reversed). Secondly, as a result of its origins in hard-floored boxing rings, not built for the bumps and falls of wrestling, luchadores almost always roll out of an impact rather than land flat on their backs or sides. And thirdly, going hand-in-hand with the tendency to roll out of impacts, aerial maneuvers are far more prevalent than they are in other styles, partially in order to make up for the lack of spectacular slams of the slower American style, and partially to emphasize competitors’ quickness and agility rather than pure strength.

Culturally, lucha libre is wildly popular in Mexico, far more than professional wrestling is in America. Legends of the ring such as El Santo and Blue Demon are revered cultural icons, men who starred in their own long-running series of films, comic books, and novels, and have passed their legacies on to new performers. Imagine if the superheroes we loved as children were more than just characters on a page, but were real, living, breathing men and women, who we could not only watch on the silver screen, but watch live, doing the kinds of things we could only dream about. That has been the impact of lucha libre on millions of people, across several generations.

PHOTO: Daniela Herrerias

But even more than that, though, lucha libre represents the people of Mexico themselves. Most performers wear masks, and often wear elaborate outfits while they make their way to the ring. In this way, they echo their Azteca ancestors who, long ago, created masks from stone, wood, and precious metals, fashioning them in the likenesses of their gods, and fierce animals such as the jaguar, donning them for religious ceremonies and before going into battle. As a warrior people, a conqueror people, the ancient Aztecas valued strength, speed, and cunning–aspects reflected amply in the modern-day luchador. To wear a mask is a luchador’s pride and honor; to lose it, or to be seen without it, is his shame. And this isn’t just hyperbole, either–the most famous luchador, El Santo, only took off his mask once, in all his years: in 1984, on the television program Contrapunto. This was the only time he would ever be seen without a mask; one week later, he would pass away, and was buried wearing the mask that he had made so famous.

So intrinsic to Mexican culture is lucha libre, in fact, that in 2018 the government of the capital of Mexico City granted it Intangible Cultural Heritage status, in accordance with UNESCO international standards. “It is a sport and a show, but also a stage performance; it is a game, magic, a theater of life with fabulous characters endowed with physical strength but also with values”, said Secretary of Culture Eduardo Vazquez. “The struggle of good and evil becomes a metaphor for life; it is a ritual, a rough and crude job that is also an art of fine execution; it is one of the most deeply rooted expressions of popular urban culture in our city and our country.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but when I saw that tape of WCW and witnessed lucha libre for the first time, I was mirroring the experiences of countless wrestling fans across America, used to the slow, powerful theatrics of American wrestling personalities. Suddenly, out of nowhere, these men in strange, colorful gear, wearing masks that hide their identities invade the ring, and proceed to showcase a kind of wrestling that heretofore I had no idea even existed. It was something of a revolution for me–and suddenly I realized that there was an entire world of wrestling out there, of all different styles, that I had never even seen. And I had that reaction watching a grainy old VHS in 1998. But for the fans these days, who get a chance to witness the athleticism, the heritage, and the spectacle of lucha libre for the first time live and in person? I can only imagine how broadly their cultural horizons will expand. At the very least, it will certainly blow their minds. As it did mine.

Folks! We invite you to also follow us through our official social media accounts:

© 2019 Lucha Central